Mastering Dungeons, Part II

May 17th, 2010

Hello everyone. Last week I talked about dungeon design, something typically more in the realm of dungeon masters than game designers. I didn’t quite get around to finishing, though, which is what I plan to do today. If you missed last week’s article you might want to go back and take a look, because some of the information below won’t make much sense without it. And, of course, if you’re here for the Eldrazi, you probably already know to look at the bottom of the page. So, without further ado…

Another step in making your dungeon both more flavorful and more realistic is to make it more dynamic. In a standard dungeon, all the monsters, traps, and NPCs sit around and wait for the PCs to walk into their room like those hallmark cards that play music when you open them, or pop-ups in a children’s book. Until the PCs encounter them, they don’t really exist. They don’t listen for the sounds of battle in the next room, and they certainly don’t rush in and actually do anything about it. They never accidentally set off their own traps, so it’s A-OK to put a complicated poison trap on the door to the barracks, for example (of course, if your inhabitants happen to be immune to poison… ). Think about what the creatures in your dungeon actually do. WHY is the medusa in that room? Is she occasionally in other rooms? Does she care enough about her bugbear cohort to come to his aid if she hears him fighting in the next room, or will she instead finish her important magical ritual?

This will make your dungeon feel more alive, and make your players feel like their actions have consequences (this is always a good thing in a game, whether it prevents your more easily-bored players from causing too much trouble, or encourages other players to act, players will only ever get frustrated if they feel that their actions don’t have a real impact on the game. For this reason, when you make a crossroads or hallway that goes in two directions, consider differentiating the two somehow. If the choice is “left or right” you might as well flip a coin, it’s arbitrary. But if one hallway has a glowing red light and the soft sound of a melancholy song comes from the other? Now THAT’s a choice. One thing you need to keep in mind with this, however, is that it will often make encounters a lot harder. If monsters are getting back-up from other rooms, you may soon find the PCs taking on virtually the entire dungeon in a single encounter. Some clever layout and dungeon design can help avoid that, but if a given encounter has much chance of triggering another encounter in the middle, take that into account when figuring out the CR, unless you really WANT a party-wipe.

Third (though really this should probably go much higher, since you’ll want to do it near the beginning… oh well, it’s not like you were sitting here building the dungeon as we went along, right?), I cannot overstate the importance of giving your dungeon a theme and sticking with it. It’s a lot less complicated than it sounds, really. The short version is, most players would prefer not to play a zoo. Yes, Fiend Folio is really cool, and yes, you do have 6 other monster manuals to choose from. I know, I read about that undead too, and I agree, he is cool. But he really doesn’t want to hang around with that gnoll barbarian, variant treant, and illithid sorcerer. And that’s just room one! Seriously, though, unless the dungeon you’re running actually is some kind of zoo, museum, or other place where you could reasonably expect a crazy mish-mash of monsters, avoid the temptation. I’ve played through dungeons like this (and probably made a few myself, in my earlier days, though I try very hard not to think about that), and in my experience they tend to hurt immersion a lot, and make the dungeon feel a little less than finished. I remember one first-time DM put together an extensive cave system which was inhabited by all different kinds of aberrations (grell, illithids, the grafting ones—zern, I think—and several others) because he had decided that they had all allied together. In his defense, he did at least provide a reason why they were all there (the aforementioned alliance) but the whole thing felt incredibly… contrived.

His second dungeon was a little better, but still suffered from a let’s-find-every-kind-of-undead-I-possibly-can-and-shove-them-all-together-itis. Set in a crypt, it sported plenty of undead, no two of which were the same. It serves to illustrate an important point, however: sometimes you really want a cool monster that just doesn’t belong there. In this DM’s case, it was a skeletal hydra. The hydra was cool (the encounter, due to spatial restrictions and a certain player who was a little too clever for his own good, was not), and deserved to stay, despite the fact that there was no real plausible explanation for there being a hydra skeleton in this small, out-of-the way crypt (for that matter, the crypt probably didn’t have a good reason for being in the middle of that field in the middle of nowhere, but we’ll let that slide) because hydras are cool. The catch is that, with a little creative thinking, you can make anything belong flavorfully. With some work, the crypt could have been the last resting place of a hero who died on the spot in an epic battle with a hydra that ended with both combatants slain. Tales of his exploits could have been written on the wall, building up and foreshadowing the hydra below. Alternatively, maybe it wasn’t REALLY a hydra skeleton at all, but was in fact some terrible amalgamation of human bones put together to form a pseudo-hydra. This could be due to some curse, or more easily be caused by a mad scientist necromancer who spent too much time worrying if he could do something and not enough time worrying if he should. Of course, if there was a necromancer in the place, he could have just brought the hydra with him (except that, in this in particular case, it wouldn’t have fit through the door), but in that case it’s important—not to mention relatively easy and cheap—to let your players know that. You never know which details they’ll latch onto, especially for one of their hare-brained schemes (you really don’t want to know the story of the purple slaad).

Fourth, be sure to add a few embellishments and garnishes. Like with fancy dishes, the garnishes here are purely for show, and serve no purpose other than to make your dungeon more appealing to players (though they can be used very effectively to give your players information about the dungeon’s history or current ecosystem). In fact, a lot of the above steps make use of embellishments in places. The only way you can show a dungeon’s history, for example, is through these embellishments. The tattered remains of a keep’s former occupants, the fact that the goblin king’s throne is made out of pots and pans that have been stuck together, or the fact that the lizardmens’ dormitories look like they were originally a prison will clue your PCs in to the details about the dungeon’s past, and even if they can’t exploit them through clever tactics (sometimes they can), they’ll still enjoy the few scraps of flavor and detail. The same goes for dynamic dungeons (though PCs expecting pop-ups will have ways besides garnishes to find out that your dungeon is dynamic, believe me!), where something as simple as making sure that the dungeon has a water source and a privy will go a long way into making it feel more realistic, as well as for a dungeon’s theme (though this is typically noted best by the absence of monsters that don’t belong, bits of explanation for monsters which are there but are more of a stretch—that skeletal hydra, for example—will go a long way). You can add other bits of flavor as well, though it’s hard to find any that can’t technically be categorized as either part of the dungeon’s history or its “dynamic-ness”. Morrowind had several memorable bits of flavor like this, starting as early as the census and excise office with the infamous note to Hrisskar pinned to the table by the knife. It’s not really important (I vaguely remember a very minor quest related to it, but I can’t recall whether or not it was added via mods), but it seems like the sort of thing one might find somewhere. The odd bit of flavor here or easter-egg there can really brighten up an otherwise dreary dungeon.

Finally—and this is probably the most important tip I can give, because, in my experience, if you can fulfill this one step most players will forgive you any other blunders you may have made—make it cool. Fun and exciting things are fun and exciting, shockingly enough, and players have a tendency to enjoy them. Over-the-top, action-packed scenes and encounters resonate well with anyone who likes that sort of thing, just like a typical intrigue-roleplayer can’t resist a scheme that’s deliciously perfect in its simplicity and elegance (and maliciousness, maybe). When you’re making encounters, try to spend a little time thinking how can I make this extra cool? An easy way to do it is usually with interactive terrain features, which can range from airships to lava pools to fighting on moving platforms or having flaming barrels of oil you can push on your opponents. In an upcoming adventure module I’m probably not supposed to tell you about, my favorite encounter involves a high-speed chariot chase. There are other ways to make things cool, of course, but giving players (and monsters) ways to interact with their surroundings is one of the easier ones. Just be sure that when you do, you take some time to consider how that interaction is really going to look at the table. What sort of check is it? What’s the effect? Is this going to be fun? Is it too powerful? Can it easily lead to a party wipe, if used against the PCs (I’m thinking about airships and lava, here)? Will they even notice it, and if not, is there a way I can draw their attention to it? Most importantly, will it be as fun at the table as it is in my head?

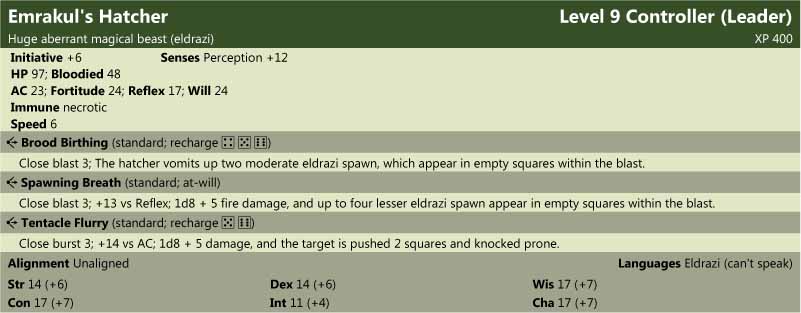

Other easy ways to make a dungeon cooler include cool treasure and a cool villain, but both of those things are outside the purview of this in particular article (though, if I get a positive response to this article, I will do more DM-advice style articles, which will likely eventually include articles about making a good villain and good treasure). In the meantime, if you really need a cool villain fix, look below for this week’s Eldrazi of the week, Emrakul’s hatcher.

As always, here he is first for Pathfinder:

Emrakul's Hatcher (CR 7)

XP 4,800

N Large aberration

Init +2; Senses darkvision 60 ft.; Perception +19

DEFENSE

AC 22, touch 12, flat-footed 19 (+2 Dex, +1 dodge, +10 natural, –1 size)

hp 115 (10d8+70)

Fort +10, Ref +7, Will +12

Immune negative energy

OFFENSE

Speed 40 ft.

Melee 6 tentacles + 11 (1d4+2)

Special Attacks Brood Birthing, Spawning Breath (30 ft cone, DC 22, 3d6 fire)

Space 10 ft.; Reach 10 ft.

STATISTICS

Str 14, Dex 15, Con 24, Int 10, Wis 17, Cha 17

Base Atk +7; CMB +10; CMD 26

Feats Alertness, Iron Will, Dodge, Lightning Reflexes, Weapon Focus (tentacle)

Skills Escape Artist +10, Perception +19, Sense Motive +10, Survival +12

Languages Eldrazi (can’t speak)

SPECIAL ABILITIES

Brood Birthing (Sp): Emrakul’s Hatcher can summon 2d4+4 Eldrazi Spawn as a standard action. This ability functions identically to the spell summon monster I except as mentioned above. The caster level is equal to the Hatcher’s hit dice.

Spawning Breath (Ex): Creatures hit by the Emrakul’s Hatcher’s spawning breath must succeed on a DC 22 Fortitude save or have their body warped by the Hatcher’s otherworldly nature. Creatures who fail their initial save must make a DC 22 Fortitude save each hour or take 1d4 points of Wisdom damage as their body and mind slowly warp and morph into an Eldrazi Spawn. A successful save does not prevent the transformation, only delay it (though a remove disease spell, or similar, can stop the effects of the corruption). If a creature’s Wisdom is reduced to 0 while under the effects of Spawning Breath, the transformation is complete and they are permanently transformed into an Eldrazi spawn with no memory of their past life. Creatures transformed in this way can be restored only through a wish or miracle spell. Emrakul’s Hatcher must wait 1d4+1 rounds between each use of this ability.

ECOLOGY

Environment any

Organization solitary or nest (2–4 plus 4d8+16 eldrazi spawn)

Treasure incidental

And now, for 4th Edition: