Gygaxian: A Definition

June 21st, 2010

Hello everyone, and let me be the first to welcome you to Gygax Week. As you may remember from Undead Week not too long ago, we’re currently toying with implementing “theme” weeks into our articles. In honor of Father’s Day, we’ve set aside this week to honor the “father of gaming,” Ernst Gary Gygax. I spent a lot of time trying to determine what, precisely, I could talk about in Dark Designs that really had anything to do with Gary. It’s hardly like I could really introduce anyone to the man—he was a public figure long before I was even born, and anyone who visits this site is at least passably familiar with the man’s work, even if they don’t know that much about him. And besides, I have no personal connection with him, no special insights to share (I did mention that we re-animated him as a zombie at some point, but it seems like poor taste to trot his corpse out here during a week set aside for him, and besides, we don’t want the zombie putting on airs). Any attempt to try and boil down the man’s career into an article would be unlikely to get you terribly much that you couldn’t find on Wikipedia, and more to the point, would probably devolve into me decrying the injustices of TSR taking the rights to Gygax’s personal D&D characters. Eventually I decided that the only option was an examination of “Gygaxian” design.

Unfortunately, I quickly found that there doesn’t seem to be much of a consensus on what Gygaxian design is. The most common use of the word I’ve heard is as a description of specific types of dungeons, and is used to describe “meat-grinders” and other wicked and devious modules which seem designed with a “DM vs the players” mindset at work. It can also be used to describe Gygax’s infamous naming conventions, especially those involving the use of his own name, subtly and cleverly altered in order to disguise it from his audience. And third, it is sometimes used to describe a more whimsical, fantastic pattern of speech affected by Gary in many of his works (as well as, in a similar vein, the care and consideration given to various tables and the description of treasures, which seem eccentric at least in hindsight, whether or not it seemed that way at the time).

So, what is “Gygaxian,” really? I won’t pretend to know. I’m not the first person to try to pin the term down, only to walk away with a feel-good non-answer about how great Gary was and how much we all owe to him. And I think we all know that if I tried to pin down exactly what “Gygaxian” means I would inevitably wind up talking about his legacy and what kind of mark he made on the gaming world, aside from being the pioneer that, well, forged it from virtually nothingness. So, instead, I accept all of those definitions, and will examine them one at a time, trying to extract from each some lesson in game design or at least DMing.

The first definition, exemplified by the Tomb of Horrors, is ultimately two issues. The first comes down to difficult and—especially—devious dungeons. Like most tools in a designer or DM’s pocket (more the DM, as, while a designer may make such a dungeon from time to time, it is the DM who eventually uses it. Really, it’s more like the designer is a smith who crafts a particularly powerful blade for a warrior—that’s the DM—who must then use the blade wisely, having great responsibility in who he cuts down and who he doesn’t) these are a good thing, if wielded appropriately. Throw your players through constant deathtraps which punish curiosity (such as the infamous green demon face, as well as basically everything else in the Tomb in question) and they’ll probably stop having fun sooner or later. Of course, an extra challenge or nasty trick now and again keeps players on their toes, and keeps the game from stagnating. I personally ran The Tomb of Horrors (updated to third edition) once, and pitched it to the players as a chance to prove themselves by surviving the epic death trap. They nearly made it, too, thanks to a healthy dose of paranoia and the foresight to pack some divination magic (not surprisingly, augury reveals the demon face as “woe”). Everyone had a blast, difficult dungeon or not, and my favorite thing about the adventure came at the end, when one of the characters used the gem of cursed wishes to wish himself home. The gem, for those not familiar, corrupts every wish in the worst way possible, doesn’t have to follow the letter of the wish like regular wishes in order to do so, and once the wish is granted it explodes in a deadly fireball. Based on the circumstances, going home seemed like the worst thing that could happen, and so the gem actually granted his wish perfectly, depositing him in his house surrounded by his beloved family, and then exploding, killing everything he held dear.

Which, I guess, brings me to the other aspect of Gygaxian dungeons: the “players vs the DM” element. Generally speaking, the gaming community has moved away from this style, and you now find that most products which discuss the fine art of DMing (my own column included) stress the role of DM more as “facilitator of fun” than as “enemy of the players.” For the most part this is for the best, and despite the style being “Gygaxian” I’m inclined to believe that the man himself would agree with me, and with the gaming community at large. I base this primarily on several of his “Up on a Soapbox” articles in Dragon Magazine, and particularly on “The Perfect Dungeon Master” from Dragon 274, where he makes it clear that, in his mind, at least, the Dungeon Master is so responsible for making sure that everyone has a good time that, if he finds himself confronted with players who “don’t roleplay enough” the fault is most likely his own, for not bringing the game to life properly. In the same article he stresses the importance of listening to your players’ suggestions and complaints. All good advice, and it is important never to let yourself forget that, ultimately, your goal as a DM is to make sure that everyone at the table has a good time. At the same time, however, it may be worth noting that the current trend of distancing DMs from the “bad guy” seat may be a little reactionary, and a good DM will need to be comfortable in that role as he will spend a lot of time in a position directly adversarial to the PCs. I should really write a column about that. Oh well, another time, perhaps.

Second, Gygaxian refers to a style of character names. More specifically, I think, it really refers to Gygax’s habit of finding ways to subtly insert his own name into various things, such as Zagyg, which, for those of you not familiar, is a reverse homonym of his name, or, in other words, it sounds the same as his last name spelled backwards. He apparently had a lot of these. Personally, I have mixed feelings about these sorts of secret add-ins. On the one hand, I’ve recently discovered a love of anagrams, and those who look closely at some of the names from the mini-adventures in The Book of Beginnings will find a handful there. Astute readers may also have noticed that “Raxen Dale,” the example wizard from my Foursaken Feature article for Undead Week, is himself an anagram of “Alexander.” These sorts of things can be a refreshing little game for designers, which helps keep them on task, and, if they’re cleverly hidden, are great fun for players who discover them. At the same time, I think it’s important to remember that ultimately these things are made for the players, and so secrets you don’t intend to reveal to them should not take precedence over, say, having a name that sounds good and invokes the right emotional response in your audience. It’s all well and good for your dragon to have a name that has a cool and appropriate meaning in draconic, but if the name sounds bad to the ear, or doesn’t sound very dragon-like, it’s not doing its job as well as if its name conjured the image of a great, terrifying, fire-breathing behemoth.

And speaking of conjuring images (my instructor at the academy always said I should have specialized in illusion magic, instead of necromancy), the third definition of “Gygaxian” has to do with his style of prose and eccentric (some have used the word “fetish”) love of tables and his attention to detail in things like treasures. Ultimately, then, this definition of “Gygaxian” translates as “flavorful.” There can be no question that his use of archaic words and phrases is a matter of flavor, a choice of wording designed to evoke images and feelings of high fantasy (and, based on how highly people speak of his prose, it’s hard to argue against his success). His tables, too, were a matter of flavor.

In a recent article about an entirely unrelated game which I happen to love very much, Doug Beyer defined flavor as “constructive simulation” (his definition may not be perfect, but he doesn’t claim it is. And besides, his job more or less revolves around flavor. He’s probably got a good idea what he’s talking about). If tables designed to allow you to randomly generate an answer to every solution isn’t the very paragon of constructive simulation, I don’t know what is. Gygax’s D&D was designed to feel like a whole and real world, and he made those tables—at least in part—in an attempt at simulating that (I came very close to saying he “constructed” the tables, but I have just enough faith in my readers to assume you made the connection on your own). Tables (and, in my opinion, flavor, to a slightly lesser degree) have been slowly being separated from D&D more and more recently, much to my dismay. This is another article I should probably write about someday, but for today I want to make sure the focus stays on Gary.

Speaking of Gary, look forward to seeing more of him this week, or at least his counterpart, Zagyg. And until next time, may the father of gaming bestow his blessing upon your dice. Oh, wait, right. The Eldrazi! Secifically, the Artisan of Kozilek.

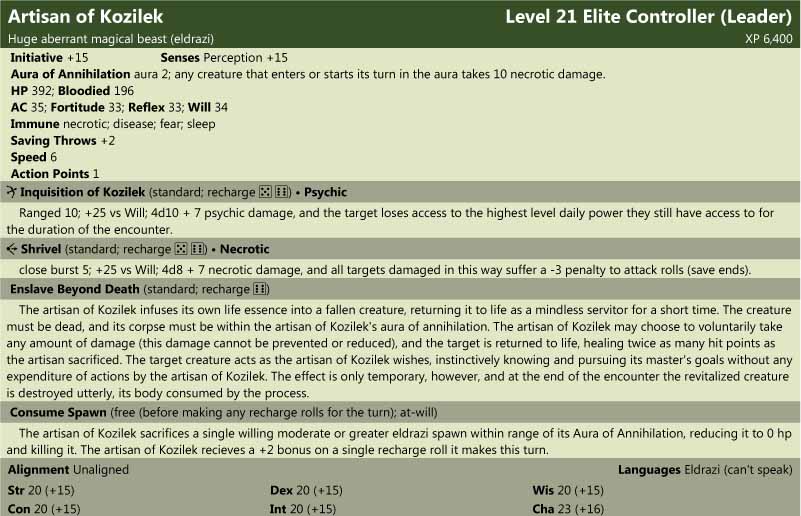

Artisan of Kozilek (CR 14)

XP 76,800

N Huge aberration (extraplanar, eldrazi)

Init +2; Senses low-light vision, darkvision, blindsight; Perception +32

Aura Aura of Annihilation

DEFENSE

AC 30, touch 10, flat-footed 28 (+2 Dex, +20 natural, –2 size)

hp 272 (24d8+164)

Fort +16, Ref +12, Will +19

Defensive Abilities rock catching; Immune critical hits, disease, energy drain, massive damage, mind-affecting, negative energy, poison, sleep, stunning SR 27

OFFENSE

Speed 50 ft.

Melee 2 slams +31 (2d6+15)

Ranged rock +20 (4d6+22)

Space 15 ft.; Reach 15 ft.

Special Attacks consume spawn, rock throwing (140 ft.)

Spell-like Abilities (CL 16th)

At will—detect thoughts (DC 18) , resist energy, see invisibility, speak with dead, tongues

3/day—blight, crushing despair (DC 19), dominate person (DC 20), enervation (DC 19), feeblemind (DC 20), lightning bolt (DC 19)

1/day—circle of death (DC 21), insanity (DC 23), horrid wilting (DC 24)

STATISTICS

Str 40, Dex 14, Con 23, Int 2, Wis 22, Cha 15

Base Atk +18; CMB +34; CMD 46

Feats Awesome Blow, Cleave, Toughness, Improved Bull Rush, Lightning Reflexes, Improved Sunder, Improved Vital Strike, Great Fortitude, Power Attack, Vital Strike

Skills Perception +32, Spellcraft +23

Languages Eldrazi (can’t speak)

SQ

SPECIAL ABILITIES

Aura of Annihilation (Su): Any living creature who moves or begins his turn within 40 feet of the Artisan of Kozilek takes 4d6 negative energy damage. For each point of negative energy damage dealt this way, the Artisan of Kozilek heals 1 hit point.

Consume Spawn (Su): As a move action, the Artisan of Kozilek can absorb the life essence stored in nearby Eldrazi spawn. The Artisan of Kozilek sacrifices a single willing Eldrazi spawn who is within range of the Artisan’s aura of annihilation, reducing the Eldrazi spawn to 0 hit points and destroying it utterly. If it does so, the DC of the Artisan of Kozilek’s spell-like abilities increases by 2 until the end of its turn.

ECOLOGY

Environment any

Organization solitary

Treasure incidental

And, for the 4e crowd...