Long Live the Villain

July 26th, 2010

Villains. Everybody loves them. Oh, sure, everybody hates them, too, but that’s not the point. A good villain, a classy villain, the kind of villain every DM wants in his or her campaign? Everybody loves that guy. Sometimes you only love to hate him, because he’s just that infuriating, and your hatred of him is what drives you through the campaign until you can finally find sweet, sweet release while standing over his slowly bleeding corpse. But a lot of the time, with really good villains, you find you really do love the character, antagonistic or no. There’s just something about how a true villain… charisma, perhaps. Or style. But with the really good ones, you sometimes find it all too easy to root for the wrong side.

Today we’ll be revisiting the topic of building good villains (that’s high-quality, not alignment-wise). There are many aspects to building a good villain, and overall it’s a topic which could take multiple books to explore, let alone trying to cram it all into a single article, so we’ll be focusing on something a little more specific today: the getaway.

Allow me to explain. You see, the best villains recur. If you only ever run across a guy once, it’s hard to really get very attached or interested in him. Since conflict in most roleplaying games is typically resolved with rather lethal force, it can be rather difficult to get a villain to come around for a second appearance, because after the first one either he’s dead, or your party is. Naturally, if you want him to be an important, recurring character, this is a bit of a problem. Luckily, there are a variety of ways around this, some more satisfying than others. I should probably note that a lot of the suggestions listed here really aren’t “getaways” in a technical sense, but they serve the same purpose, which is to make sure that your villain ultimately survives to plot another day.

Method 1: Avoid Fighting

I’m going to say up-front that, unless handled very carefully, this will probably not go over well with your players. I’m sure you’ve seen a movie, read a book, or, most likely, even played a video game where the main character, after cutting a bloody swathe through hordes and hordes of mooks and minions, finally makes his way up to his foe… only to find himself there moments too late, watching helplessly as the smug bastard rises from the scene on a rope-ladder hanging from a helicopter, or the doors close on the escape pod, or he simply teleports to safety as soon as the PCs get within 1,000 feet. You get the idea. Taunts may or may not be exchanged, as desired.

This can be a very tempting thing to do, as it tends to be relatively powerful in books and movies, making for memorable scenes as the hero curses his luck for being seconds too late, probably taking out his frustration on something nearby. Unfortunately, these feelings tend not to translate well to tabletop.

The frustration created by taunting the PCs with a chance at fighting the big bad and then taking it away from them when they seemed so close can be a powerful tool in getting your players to hate your villain, but if you aren’t very careful it will quickly turn to apathy towards the entire game—after all, once it becomes clear that you aren’t going to allow them to fight the bad guy until you decide it’s “time” for that, the players aren’t really going to feel like they’re driving the story, or that their decisions and actions have much of an impact. It may not be long before they stop being frustrated with your villain and start being frustrated with you.

On the other hand, you can get quite a bit of mileage out of your villain without ever putting him “on stage,” if you do things right. Rather than have the PCs come into direct conflict with the villain, let them come across his reputation, or minions, or (better yet) both. Baldur’s Gate provides a good example, here: with one minor exception, you don’t come face-to-face with the bad guy until the game is almost over. And yet, by that time you will have accumulated so much hatred and found so many things to want revenge for that it will seem like he’s been there the whole time. How is this accomplished? A couple of ways. First, he’s part of an organization, meaning that even though you haven’t been fighting him, you’ve been fighting his men for the vast majority of the game. Of course, if the PCs don’t know that those bandits are working for your big-bad-end-boss you won’t get the mileage you’re looking for. This can be done as simply as giving the organization a name and putting your villain at the top (and secretly smiling inwardly every time the PCs start questioning henchman about who’s calling the shots) or as ham-fistedly as having them mention him directly. If they mention him with awe or fear, you can give him a reputation, while you’re at it. Either way, uniforms, emblems, and the like can help your PCs spot “the bad guys” from a long ways off.

Alternatively, your villain could be the type that simply doesn’t fight. We all know about the “untouchable” crime lord who happens to know the right people, is politically important, or otherwise can’t just be assaulted. In this case, though, you’ll need to make sure that he has muscle on hand at all times (or a lot of protection), because I promise you that your PCs will only take “diplomatic immunity” lying down for so long.

Method 2: Fight and Run

Another time-honored classic involves the villain wading into combat… only to find himself losing, at which point he decides to cut his losses and flee. In my experience, this is the favored way of handling recurring villains in D&D: it allows the players to interact with the villain, then saves him to fight another day. Unfortunately, it’s not very satisfying. If you thought that not getting to fight the villain might be frustrating, imagine what happens when victory is wrenched from your grasp just when it looked like you were going to win. Besides, he loses a lot of his “cred” once the PCs know that they can beat him.

Worse still is the time-honored RPG tradition of the “too early” fight. You’ve probably seen it somewhere, but if you haven’t, it goes something like this: the PCs go up against the villain, only to discover that he’s miles outside their league. They can’t hit him, or, if they do, it barely leaves a scratch. Worse still, he cuts through their defenses like butter, and it doesn’t take long to see that the fight is hopeless. Then, to add insult to injury (and certainly not so that the PCs can survive, level up, and eventually beat the baddie) the villain sneers contemptuously, declares that the PCs are beneath him, and then heads off to do villainy things, leaving the party sprawled half-conscious across the floor.

Personally, I think that this method should be avoided at all costs. For one, it’s been done to death: your party’s seen it and, frankly, they don’t really care anymore. For another, while it does have the benefit of “building up” your villain (which is desirable), it comes with the drawback of “tearing down” your party (which is generally not desirable, at least if you want your players to have fun). You can get all the same benefits (and maybe a little more) without any of the drawback if you give the process a slightly more complicated set-up: have the villain beat somebody else. If the PCs know that, for example, trolls are a little ways out of their league, then finding out that the villain can kill a dozen trolls single-handed will give them the same message that the villain’s out of their league, without any hard-to-explain mercy or deliberate deconstruction of the character’s worth.

Still, if you want your villain to hit-and-run, D&D provides you with a bevy of options, most of them in the form of spells: invisibility works in a pinch, though dimension door and teleport are generally surer things (all three available in magic item form, for non-spellcasters). Gaseous form does surprisingly well, especially if it comes from being a vampire instead of a spell (last time I checked, at least, the vampire version was flat-out immune to damage, rather than just having DR). At lower levels, even something as simple as a fly or swim speed will do the trick. My favorite is probably creative use of stone shape.

Method 3: Distraction

Throw a bigger and more immediate concern in front of your players (or, better yet, have your villain do it himself) and force them to choose between getting their vengeance and saving the day. Let’s face it, you’ve seen this one too. It’s a classic in superhero movies, typically involving a train or bus full of people. There are other options, of course: a time-triggered event set to go off at the other end of town, a cave-in, a beloved NPC dangling by a fraying rope over a vat of lava-sharks, etc. Some are more cliché than others.

This allows the PCs to “win” by dealing with the sudden crisis, allowing them to feel good about themselves and not feel cheated by your desire to let the villain get away. At the same time, the villain gets away. Everybody wins.

The biggest potential problem here is that the PCs won’t take the bait: not everyone who comes to the table wants to play a comic book superhero, and, especially the third or fourth go-round, you might be surprised how many players would rather get vengeance than save the day. If this happens, you basically have two options: you can either accept that that villain just wasn’t meant to be and go on to create an even better, more enjoyable, cooler, and generally better-defended villain, or you can retroactively apply method 4. In the case of the latter, be careful not to give away to your players that this was a change of plans: they’ll feel cheated, and rightly so.

Method 4: Die to Fight Another Day

This is by far my favorite method. It keeps the villain safe and completely in control, allows the PCs to fight him or her, and even let them win… only to come back again later. Obviously, if coming close to a fight only to have it snatched away is frustrating, and nearly winning only to have it snatched away is even more frustrating, it stands to reason that actually winning and having it snatched away would be worse still, right?

Yes and no. If you’re careful with it, it plays brilliantly. One of the important things about this method is to get the players to see the challenge not as beating the villain, but finding a way to dispatch him permanently. But, I get ahead of myself. The method?

It varies, of course. But the core principle is the same: killing the bad guy isn’t enough. He just gets back up and tries again. Sound like it breaks the rules? Think again. Vampires, liches, clone, raise dead, resurrection, reincarnate, magic jar (and, by the same token, my own Helm of Possession) all can create this effect. In fact, one of my favorite adventure twists (second, in fact, after a twist involving a petrified princess) that I’ve used as a DM involved a lich who had lost a war and been sealed in a tomb, far, far away from his base of operations. Rather than make the long and laborious trek back to his tower, or cave, or whatever kind of dark abode it was (this was quite some time ago) he simply made it known where he was, waited for some holy warriors (the PCs) to come along, and pretended to make a good fight of it. They killed him, and he reformed exactly where he wanted to be.

This method lets the PCs cross blades with the bad guy as often as you like, lets them win or lose as necessary, and, as long as you don’t make the PCs feel like the villain will actually be impossible to dispose of permanently, they can pursue a quest to that end, not feeling like each fight with the villain is a pointless waste of time as they all dance on the DM’s puppet strings.

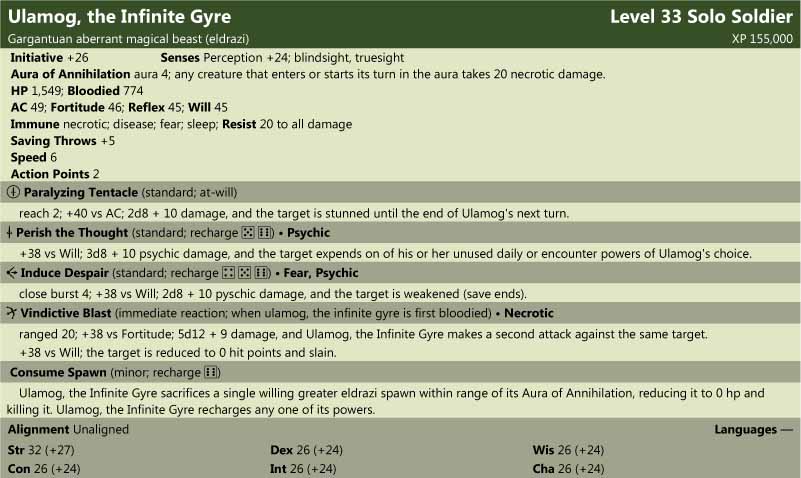

Until next time, may your escape pod never be out of service when you need it. And speaking of needing to escape, I'd like to introduce you to my pal Ulamog, the Infinite Gyre.

Now available in both Pathfinder and 4e flavors!

Ulamog, the Infinite Gyre (CR 23)

XP 820,000

N Colossal aberration (extraplanar, eldrazi)

Init +2; Senses low-light vision, darkvision, blindsight; Perception +32

Aura Aura of Annihilation

DEFENSE

AC 33, touch 8, flat-footed 31 (+2 Dex, +25 natural, –4 size)

hp 459 (34d8+306); regeneration 10 (special)

Fort +19, Ref +15, Will +24

DR 25/epic; Immune critical hits, disease, energy drain, massive damage, mind-affecting, negative energy, poison, sleep, stunning ; Resist acid, cold, electricity, fire, and sonic 15; SR 48

OFFENSE

Speed 50 ft.

Melee 2 slams +40 (2d6+19)

Space 30 ft.; Reach 30 ft.

Spell-like Abilities (CL 20th)

Constant—mind blank

At will—detect thoughts (DC 20) , enervation (DC 21), lightning bolt (DC 20), resist energy, see invisibility, speak with dead, tongues,

3/day—blight, crushing despair (DC 21), dominate person (DC 22), feeblemind (DC 22), finger of death (DC 24), insanity (DC 24), reverse gravity

1/day—circle of death (DC 23), energy drain (DC 26), insanity (DC 24), horrid wilting (DC 25), meteor swarm (DC 26), power word kill

STATISTICS

Str 48, Dex 14, Con 27, Int 2, Wis 24, Cha 15

Base Atk +25; CMB +49; CMD 61

Feats Awesome Blow, Cleave, Toughness, Improved Bull Rush, Lightning Reflexes, Improved Sunder, Improved Vital Strike, Great Fortitude, Power Attack, Vital Strike

Skills Perception +32, Spellcraft +23

Languages Eldrazi (can’t speak)

SQ

SPECIAL ABILITIES

Aura of Annihilation (Su): Any living creature who moves or begins his turn within 80 feet of Ulamog, the Infinite Gyre takes 4d6 negative energy damage. For each point of negative energy damage dealt this way, Ulamog heals 1 hit point.

Regeneration (Ex): The only thing proven to stop Ulamog’s regeneration is negative energy of the sort that causes energy drain and level loss. Though Ulamog is immune to energy drain, for each negative level that Ulamog would gain, instead his regeneration is interrupted for one minute. This effect overlaps (does not stack) with itself, so if Ulamog would gain four negative levels in a single round, his regeneration only stops for one minute, but if it would gain one negative level every minute, the effect could be prolonged indefinitely.

ECOLOGY

Environment any

Organization solitary

Treasure incidental

And, for 4e fans...